Parsing the Unparseable: Inaccessible SBNK Instruments

First blog post!

I’m just going to talk about things that interest me here. Maybe they’ll interest someone else, too. For this first post, I’ll explain one of the more interesting programming problems I’ve encountered and how I solved it.

SDAT and SBNK

Let’s begin with a quick oversimplified primer on what SDAT and SBNK are. You can skip this section if you already know about them.

SDAT is a file format used in many (though not all) Nintendo DS games. A single SDAT file can contain all of the music and sound effect data for an entire game, though some games have several of them. It’s the predecessor of BRSAR on the Wii, BCSAR on the 3DS, and BFSAR on the 3DS, Wii U and Switch. It can be roughly thought of as a container that can hold lots of files of several different types.

SBNK is one of the types of files that can be found within an SDAT. It represents a “sound bank,” which, loosely, defines instruments (AKA “patches,” if you’re familiar with MIDI terminology) that can be used in music and sound effects. These are ultimately just fancy blobs of metadata that point to the actual sound files.

That should be enough to follow along with the rest of this post. If you’d like some more detailed information, I wrote a longer document explaining SDAT here.

Also, when looking at the diagram images, please keep in mind that multi-byte values in SDAT files, as in most Nintendo DS file formats, are in little-endian byte order.

The beginning

ndspy, my Python library for working with various Nintendo DS file formats, actually began life as a SDAT library, which is why its support for SDAT is so thorough. One of my goals was to represent everything accurately enough that unpacking and repacking any file from a retail game will result in the exact same file data as before, byte-for-byte. SBNK, however, presented a unique challenge to this.

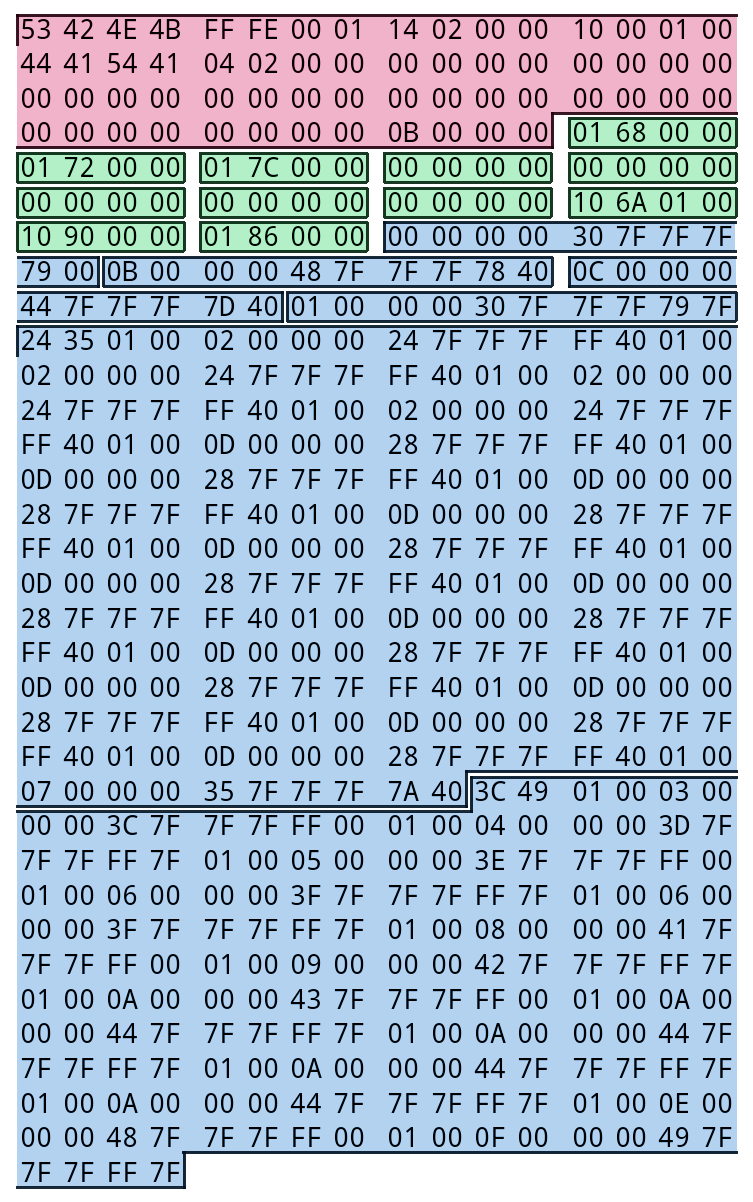

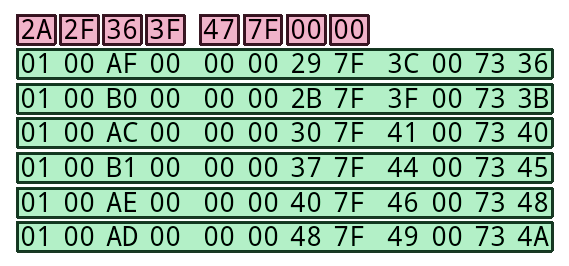

Let’s take a look at how SBNK files are structured. Here’s an example (BANK_ST04 from Mario Hoops 3-on-3):

- (in red) The file begins with a header struct, which, among other things, defines how many instruments there are. In this case, there are 0xB (11) of them.

- (in green) That’s followed by an array that the game uses to look up instruments by ID. Each element is 4 bytes long, and contains an instrument “type” value (first byte) and an offset to its actual data struct (next two bytes).

- (in blue) Finally, we have the actual instrument data, which the offsets in the above table refer to. The length and format of the data for each instrument depends on its type. There are three types:

- Single-note instrument: plays the same sound file regardless of the note’s pitch. Most often used for “instruments” that are actually sound effects.

- Range instrument: divides the range of allowed note pitches into sections (regions), each of which corresponds to a different sound file. Most often used for… normal, pitched instruments.

- Regional instrument: uses a different sound file for every pitch value in some range X to Y. Most often used for drumsets.

The data section (the blue one) is what we’ll mainly be focusing on.

The problem

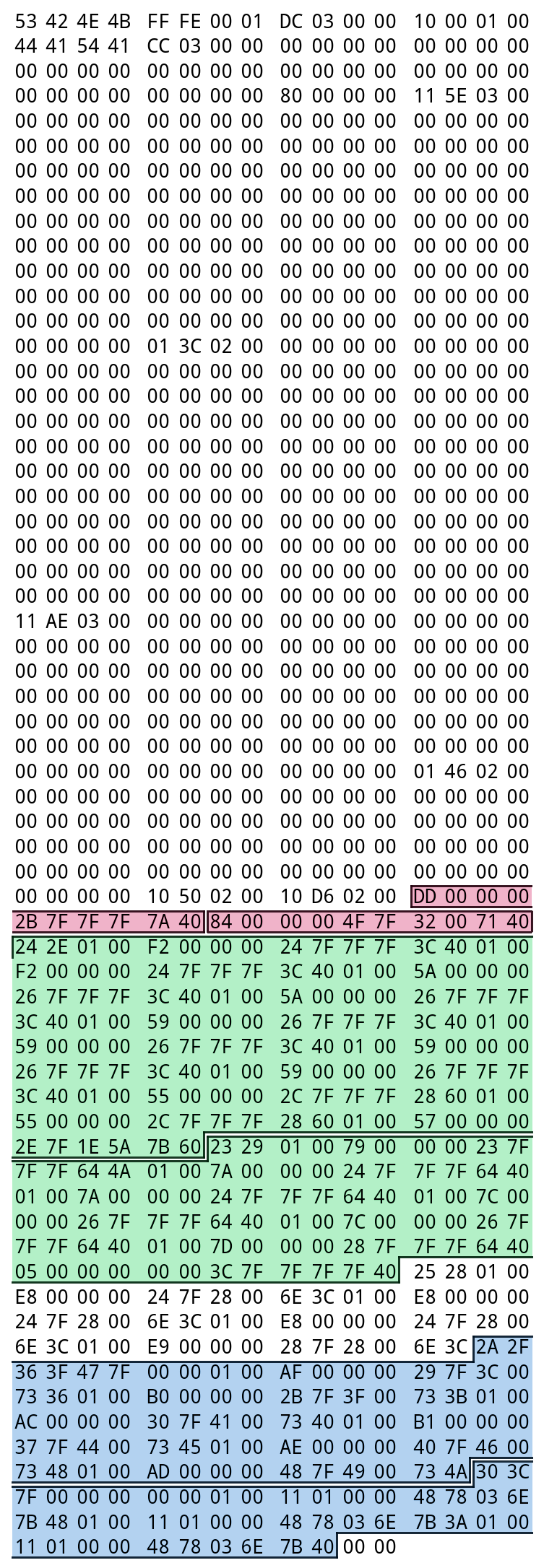

All of the above is pretty well-documented online, and not too difficult to implement a parser for. At first, all was well. I began running into problems, though, when I tried my code on files such as BANK_MUS_DOSUN_IN from Mario & Luigi: Partners in Time. That file looks like this:

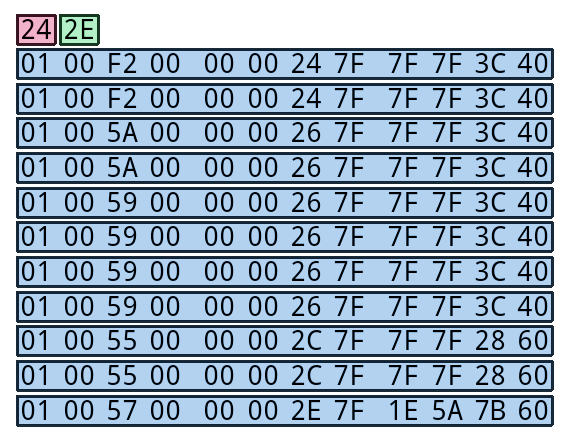

The highlights here show the individual pieces of instrument data, as declared by the offsets table just above it. Red means single-note instrument, green means range instrument, and blue means regional instrument. Everything above the first highlighted region is the header and the offsets table, which are unimportant for the moment.

The problem is that there’s a bit of instrument data in the middle that doesn’t seem to be referenced by anything in the offsets table. My code was (of course) ignoring it, and thus omitted that when re-saving, causing my tests to fail. Strange.

(There’s also a couple of unused bytes at the end, but that’s just because all SBNK files are zero-padded until they’re a multiple of 4 bytes long. No mystery there, and that’s easy to implement in code.)

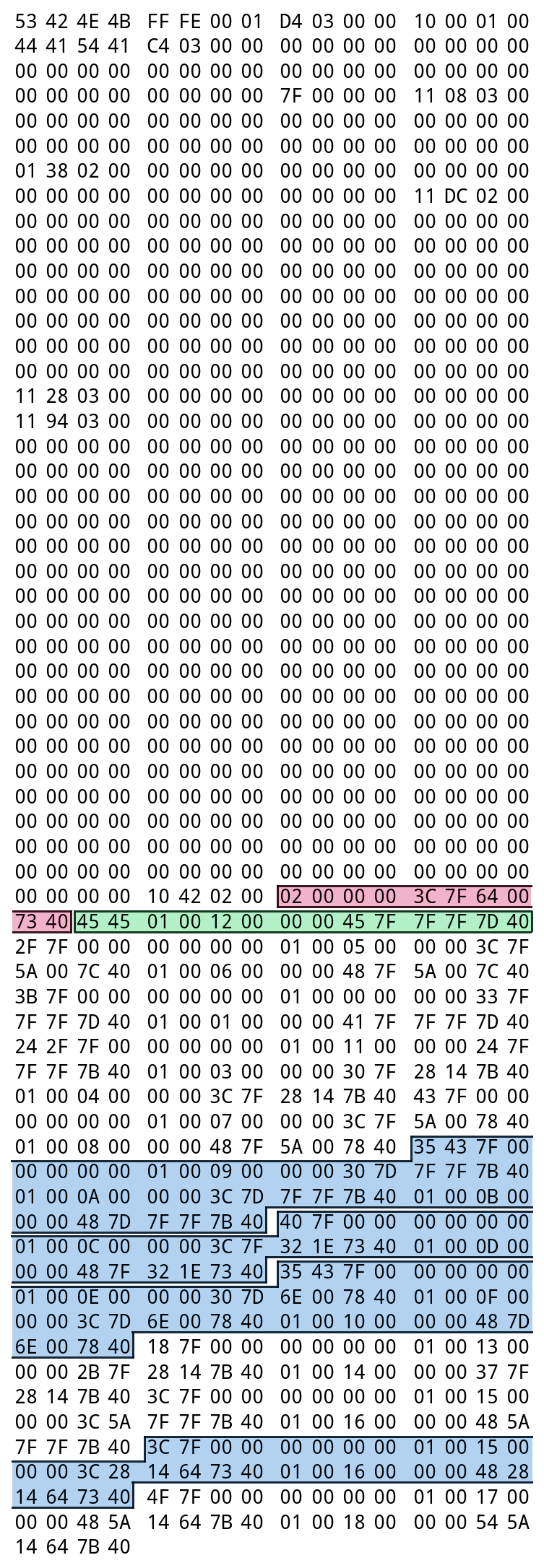

Doing some more research on this, I found more examples of similar files, such as BANK_BGM_FIELD_HOSPITAL from Pokemon Ranger: Guardian Signs (on the right). This one is even worse! This file actually has more unused instrument data than used data.

At this point I began to thoroughly investigate these files containing mystery data (in all, I was able to find about 70 of them), trying to find anything that might tell me why it was there. Perhaps there was some previously undiscovered value somewhere that made instruments act like arrays, or something like that. Unfortunately, though, nothing turned up. Every nonzero byte was accounted for.

Eventually I came to accept that that this instrument data was most likely truly unused. I think what probably happened is the following:

- SBNKs in official games were created by using some tool that converted them from a plain-text format (XML? I hear Nintendo likes using XML for that kind of thing) to the binary format.

- These text files contained the instrument parameters and the ID-to-instrument mapping tables separately, just like in the binary files.

- The official conversion tool wasn’t smart enough to recognize instruments that weren’t assigned an ID.

- Some developers accidentally left such unassigned instruments in their files now and then, and they wound up in the binary files.

So while these unreferenced instruments exist in some SBNK files, games can never access them, as far as I know.

For completeness (and that whole byte-for-byte-accurate-resaving thing), I wanted ndspy to be able to recognize and keep track of this data (albeit separately from the main instrument data, of course). This turned out to be more challenging than I anticipated, though. While it’s easy enough to identify parts of the instrument data that don’t get read during normal parsing, there’s a big problem when you then try to actually read that data: the data format depends on the instrument type, and the instrument type is stored in the header table, but unreferenced instruments don’t have entries in that table! So, how can we read the data without knowing the instrument type?

We guess the type.

The solution

OK, so we’re going to guess the type of each unreferenced instrument. At the time of this writing, the code that does this in ndspy is split between the SBNK._initFromData() and guessInstrumentType() functions. The goal of this blog post is to walk through the steps of this process, since I think it’s kind of interesting. I’ll also include actual code snippets from ndspy where it makes sense to, though you can ignore them if you want.

Let’s start by defining the problem more specifically. As input, we only know the following:

- where a particular run of unreferenced instrument data begins

- the length of this run of data (which may contain multiple instruments in a row, but we don’t know if that’s the case yet)

- the positions and types of the known instruments in the file

The goal is to identify the type of the instrument at the beginning of this run. We can then repeat this algorithm a few times until no unknown instrument data remains.

The basic idea is that we start by assuming that all three instrument types are possibilities, and then attempt to rule each of them out using increasingly aggressive metrics until only one option remains. As soon as we’ve narrowed it down to one choice, the algorithm immediately terminates.

Facts

What metrics do we use, then? For best results, it’s best to start with the most accurate ones we can think of, and only start using less accurate ones if we really need to. What do we know for sure about these unknown instruments?

If you look at the images above, you’ll notice that the instrument data seems to be sorted by instrument type. As it turns out, that always holds true. Thus, the first thing we do is check the types of the known instruments preceding and following the mystery data. For example, if our unknown data is preceded by a range instrument, and followed by another range instrument, we immediately know that we’re looking at a range instrument – no guessing required.

(I’d include a nice code snippet here, but the code for this check is rather complicated and ugly compared to the intuitive explanation above. Sorry.)

This simple check actually allows us to determine the instrument type in about 60% of real cases. That’s a good start, but for cases where the unknown data lies between two different instrument types, we need to go further.

The next thing we check is the amount of contiguous data. The data for a single-note instrument is always 10 bytes long, range instrument data (containing at least one range) is at least 14 bytes long, and regional instrument data (with at least one region) is at least 20 bytes long. So if we have, say, 14 contiguous bytes of data, we can, at the very least, rule out the regional type.

if bytesAvailable < 10:

ruleOut(NO_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

if bytesAvailable < 2 + 0xC:

ruleOut(RANGE_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

if bytesAvailable < 8 + 0xC:

ruleOut(REGIONAL_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

By adding this metric, our detection rate increases by… 0%. Yeah, this check doesn’t actually seem to help whatsoever in practice. That’s kind of disappointing, but I left it in anyway because it’s the only other test we can do that’s guaranteed to at least be accurate.

To classify the remaining 40% of unknown instruments, we need fall back to weaker tests. We’ll rely on empirical properties of each instrument type that don’t strictly have to be true, but usually are. We can use these to try to pare down the remaining options until there’s only one left.

Heuristics: single-note instruments

Let’s try to rule out the possibility of the instrument being of the single-note variety.

As an example, here’s one of the single-note instruments from BANK_MUS_DOSUN_IN, highlighting the SWAV ID, SWAR ID, pitch value, and a blob of rather less interesting stuff. We’re going to run some tests to see if our unknown data does or does not look like this.

The first thing we can check is its SWAV and SWAR IDs. You don’t really need to know what these values represent; just know that they’re two-byte-long integers at the beginning of the single-note instrument data struct. There’s a limit to how big these numbers get in practice, so if we see suspiciously large values there, we can conclude that the unknown data is probably not a single-note instrument. In my collection of games, SWAR IDs tend to be on the order of two or three decimal digits long; the record, though, is 2290 (Pokemon White 2). Similarly, most SWAV IDs are one or two digits long, with the record being 969 (The Legend of Zelda: Spirit Tracks). For ndspy, I chose 2560 (0xA00) as the limit. If the values we see are larger than that, we rule out the single-note instrument type.

# Among the games I've looked at, SWAV ID and SWAR ID are never

# each more than 0xA00, so we can use that as a reasonable limit

if data[startOffset + 1] >= 10: ruleOut(SINGLE_NOTE_PCM_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

if data[startOffset + 3] >= 10: ruleOut(SINGLE_NOTE_PCM_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

We next check the instrument’s pitch. For single-note instruments, pitch is encoded as a single byte at offset 0x4. Middle-C is represented by the value 60, and actual used values are probably roughly normally distributed around that. In particular, almost no single-note instruments have a pitch of 0 (about a hundredth of a percent of them do, and all of those happen to be in Yoshi’s Island DS). So let’s say that if we see a zero in this position, we’re almost certainly not looking at a single-note instrument.

# And pitch will probably never be 0, right?

if data[startOffset + 4] == 0: ruleOut(SINGLE_NOTE_PCM_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

However, about 77% of single-note instruments have middle-C (value 60) as their pitch. So if we see a 60 there, that’s rather strong evidence for this being a single-note instrument. In that case, ndspy immediately concludes that this probably is a single-note instrument, and the algorithm ends right there.

# For that matter, if pitch is 0x3C (middle C), we can probably

# just assume straight away that this is a single-note inst

if data[startOffset + 4] == 0x3C:

return SINGLE_NOTE_PCM_INSTRUMENT_TYPE

Heuristics: range instruments

If there are still multiple possibilities at this point, we next try to rule out range instruments.

Here’s one of the range instruments from BANK_MUS_DOSUN_IN, highlighting the “min” and “max” values, and each of the note definitions following them. (You may notice that the number of note definitions is max - min + 1.) What can we look for to see if the unknown data is in this format?

The first two bytes are “min” and “max” values that define the pitch range. If min > max, this probably isn’t a range instrument, so we rule this type out.

firstPitch, lastPitch = data[startOffset : startOffset+2]

if firstPitch > lastPitch:

ruleOut(RANGE_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

The amount of instrument data is determined by max - min. We can use this difference to calculate how long the data ought to be; if the amount of contiguous unknown data is less than that, we rule out this instrument type.

expectedLen = 2 + 0xC * (lastPitch - firstPitch + 1)

if expectedLen > bytesAvailable:

ruleOut(RANGE_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

Heuristics: regional instruments

If there are still multiple possibilities, we finally try to rule out regional instruments.

Here’s one of the regional instruments from BANK_MUS_DOSUN_IN, highlighting the eight maximum-pitches values, and each of the note definitions following them. When trying to prove that the unknown data isn’t structured like this, what should we look for?

The first eight bytes are the maximum pitch values for each region (of which there are 8 or fewer). These values are strictly increasing, up to the value for the last region, which usually (but not always) has the value 0x7F. If the instrument has fewer than 8 regions, the remaining bytes are all set to 0. (Notice that in the example above, there are six nonzero maximum-pitches values, and six note definitions.) If the first 8 bytes of the unknown instrument data don’t satisfy this pattern, we rule out the regional instrument type.

(The code for that heuristic is 19 lines of ugliness, so I’m not reproducing it here.)

Secondly, similarly to what we did for range instruments, we use the maximum-pitches list to count how many regions there should be, and from that, calculate how much data the instrument should have in total. If the amount of contiguous unknown data is less than that, we rule out regional instruments.

# Finally, check that we have sufficient length

regionCount = 0

for e in regionEnds:

if not e: break

regionCount += 1

expectedLen = 8 + 0xC * regionCount

if expectedLen > bytesAvailable:

ruleOut(REGIONAL_INSTRUMENT_TYPE)

Ending

If the data somehow managed to pass all of these tests without getting classified, we throw up our hands at this point and pick one of the remaining possibilities more or less at random. In practice, though, the algorithm never reaches this point when tested on real cases – it always makes its decision somewhere earlier.

Conclusion

Guessing the type of a piece of data with a somewhat unknown structure is a rather unusual and interesting problem. Although there’s no perfect way to accurately measure how good this algorithm is, it’s good enough that all SBNK files I’ve tested it with can be resaved with byte-for-byte accuracy. Since different instrument types have different data lengths, and ndspy doesn’t keep track of any SBNK data it’s unable to classify as an instrument, this just about guarantees that ndspy is probably classifying unknown instrument data correctly 100% of the time.

Since this algorithm is rather ad-hoc and merely based on my own observations and guesses, there are a lot of ways that the process could be made more precise and accurate:

- Instead of trying to rule out different instrument types one by one, it could give each one some sort of likelihood score, and select the type that has the highest score at the end.

- Or perhaps one could perform statistical analyses on what values are most likely to occur at different byte positions for different instrument types, and compare the byte values of unknown instruments to those models to see which one fits the data the best.

- Going deeper still, this problem seems like the kind of thing that could potentially be well-suited for machine learning…

The problem with all of these proposals is, do you have any idea how overkill they would be? Remember that there are literally no known uses for this inaccessible instrument data, and my existing algorithm already has a 100% success rate on all real cases I can find. There are much better things I can choose to spend my time on.

Like writing blog posts, I guess.